The British Army and the Irish Republican Brotherhood

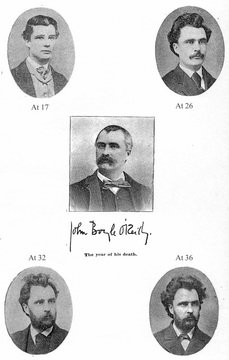

O'Reilly at various stages of his life (Donahoe's Magazine, 1896)

O'Reilly at various stages of his life (Donahoe's Magazine, 1896)

O’Reilly was born in the Meath village of Dowth during 1844 to Eliza Boyle and William David O’Reilly. William David was a local national school teacher while Eliza managed an orphanage on the grounds of Dowth Castle, long-time home to the Netterville family. John’s parents were thus able to spare the family from the worst ravages of the Famine years. O’Reilly remembered his childhood as a happy time, although when an older brother became ill with tuberculosis the eleven year old John took a job with a local newspaper, the Drogheda Argus. There he worked as a printer’s devil; a dogsbody who carried boxes of type, kept the printing office clean, and who assisted the printers in their work. O’Reilly remained in the Argus for four years until 1859. That year the paper’s owner died and the fifteen year old was released from his apprenticeship. O’Reilly’s unemployment was to be brief. In August of that year the O’Reilly homestead played to host James Watkinson, an English cousin. Watkinson was married to Eliza Boyle’s sister and he invited John to accompany him back to Preston. O’Reilly would spend four years in the Lancashire town, working as a reporter with the Preston Guardian.

By O’Reilly’s own account it was a happy time for the Irishman but in 1863 he returned to Ireland. Why he made this decision is uncertain but, like many other Irish men of the time, O’Reilly was drawn to a military career. He volunteered for service in the British army, joining the Tenth Hussars, a cavalry regiment famed as ‘The Prince of Wales’ Own’ due to the presence of the future King Edward VII among its officers. The regiment was stationed in Ireland and O’Reilly was to spend much of his enlistment at Islandbridge Barracks (later known as Clancy Barracks) on the south bank of the River Liffey. The Irishman was a talented and popular soldier. ‘The best young soldier in the regiment’, declared one officer.

Yet, O'Reilly was living a double life that would have shocked his officers. In October 1865, O’Reilly became an active member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. That revolutionary group, more commonly known as the Fenians, was stealthily advancing its plans to overthrow British rule in Ireland. Its leader, James Stephens, had given a twenty-three year old Kildare man, John Devoy, the task of recruiting Irish soldiers in the British army into the Fenians. Through this work Devoy made contact with O’Reilly, whom he described as ‘a handsome, lithely built young fellow’, and drew him into the planning of the rebellion. Why O’Reilly decided to become an active Fenian at this stage is unclear. He may well have been influenced by the successful Fenian newspaper, the Irish People which was then very popular in Ireland. Also, his older brother, William, was a Fenian and it may be that the family were active supporters of the movement.

By O’Reilly’s own account it was a happy time for the Irishman but in 1863 he returned to Ireland. Why he made this decision is uncertain but, like many other Irish men of the time, O’Reilly was drawn to a military career. He volunteered for service in the British army, joining the Tenth Hussars, a cavalry regiment famed as ‘The Prince of Wales’ Own’ due to the presence of the future King Edward VII among its officers. The regiment was stationed in Ireland and O’Reilly was to spend much of his enlistment at Islandbridge Barracks (later known as Clancy Barracks) on the south bank of the River Liffey. The Irishman was a talented and popular soldier. ‘The best young soldier in the regiment’, declared one officer.

Yet, O'Reilly was living a double life that would have shocked his officers. In October 1865, O’Reilly became an active member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. That revolutionary group, more commonly known as the Fenians, was stealthily advancing its plans to overthrow British rule in Ireland. Its leader, James Stephens, had given a twenty-three year old Kildare man, John Devoy, the task of recruiting Irish soldiers in the British army into the Fenians. Through this work Devoy made contact with O’Reilly, whom he described as ‘a handsome, lithely built young fellow’, and drew him into the planning of the rebellion. Why O’Reilly decided to become an active Fenian at this stage is unclear. He may well have been influenced by the successful Fenian newspaper, the Irish People which was then very popular in Ireland. Also, his older brother, William, was a Fenian and it may be that the family were active supporters of the movement.

'I wrote these slips before I knew my fate, and I have nothing more to say, only God's holy will be done! If I only knew that you would not grieve for me I'd be perfectly happy and content.'

- O'Reilly to his parents while awaiting his Court Martial, 1866

Arrest and Imprisonment

A sketch of a prisoner in Millbank

A sketch of a prisoner in Millbank

Whatever the reasons for O’Reilly’s activism it is clear that the young soldier was a prodigiously successful recruiter. His infectiously helpful and friendly personality was the key to his success. Throughout his life we see how O’Reilly was able form friendships in almost any situation and with people from diverse political, religious and racial backgrounds. Michael Davitt, a good friend of O’Reilly in later years, wrote that: ‘It would be impossible for O’Reilly to be anywhere on earth where human beings congregated without making friends’. O’Reilly used his amiable personality to help persuade most of the Irish soldiers in the Hussars, some eighty men, to take the Fenian oath which required that they devote themselves to the creation of an Irish republic. Each oath-taker was to continue with his army duties but when the moment for action arrived, when the promised revolution took place, they were to join with the rebels.

This double life carried substantial risks for O’Reilly. The British Government and its Dublin Castle officials were aware that the Fenians were preparing for war and so they sought to infiltrate the revolutionary group through the use of informers. Such men proved devastating to the Fenians. Dublin Castle was especially keen to locate those, such as O’Reilly, who were working as Fenian agents. O’Reilly’s success now proved his undoing and he was implicated by some of his recruits within the Hussars. He was arrested by the police in February 1866 amid scenes of much rancour. ‘Damn you, O’Reilly! You have ruined the finest regiment in Her Majesty’s service’ shouted one officer as the young soldier was marched from Islandbridge. O'Reilly was court-martialed later that year and found guilty of treason, then sentenced to twenty years penal servitude. Over the next few years O'Reilly was moved through a succession of English prisons, experiencing contemporary penal practices such as the separate system and the silent system.

This double life carried substantial risks for O’Reilly. The British Government and its Dublin Castle officials were aware that the Fenians were preparing for war and so they sought to infiltrate the revolutionary group through the use of informers. Such men proved devastating to the Fenians. Dublin Castle was especially keen to locate those, such as O’Reilly, who were working as Fenian agents. O’Reilly’s success now proved his undoing and he was implicated by some of his recruits within the Hussars. He was arrested by the police in February 1866 amid scenes of much rancour. ‘Damn you, O’Reilly! You have ruined the finest regiment in Her Majesty’s service’ shouted one officer as the young soldier was marched from Islandbridge. O'Reilly was court-martialed later that year and found guilty of treason, then sentenced to twenty years penal servitude. Over the next few years O'Reilly was moved through a succession of English prisons, experiencing contemporary penal practices such as the separate system and the silent system.

'Better the old dungeon, with its gloom; better for the sake of humanity. The new prison is a cage - a hideous hive of order and commonplace severity, where the flooding sunlight is a derision, and the barred door only a securer means of confinement.'

- O'Reilly describing life in Millbank Prison, 1878

Return to Top of Page