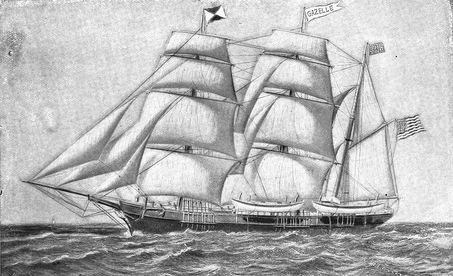

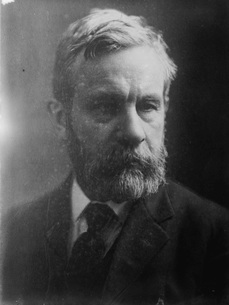

Henry W, Grady, 1889 (US Library of Congress). O'Reilly was very critical of Grady's advocacy of the 'New South'. Henry W, Grady, 1889 (US Library of Congress). O'Reilly was very critical of Grady's advocacy of the 'New South'. In 1883, the US Supreme Court ruled that the 1875 Civil Rights Act was unconstitutional, in what proved to be a devastating decision for African-Americans, especially those in the south. The Act of 1875 had prohibited racial discrimination in public places and its repeal severely limited the power of the federal government to guarantee equal status under the law to blacks. State legislatures throughout the south took advantage of the ruling to enact laws that legalised racial segregation in public places, such as schools, hospitals, and restaurants. Such discrimination had many defenders, especially the eloquent and highly influential southern orator Henry W. Grady. The southerner toured the United States in the late 1880s making speeches on what he called the ‘New South’. In these speeches he claimed that the northern media had had overplayed the poor relations between whites and blacks in southern states. Grady’s speeches were about more than race-relations; he also stressed the need for the south to industrialise and make itself a vital part of the United States. Those features of Grady’s thinking were laudable but his analysis of the ‘race problem’ was wilfully misleading and utterly supportive of a society that was grotesquely prejudiced against blacks. In December 1889 Grady spoke at Faneuil Hall in Boston on ‘The Race Problem in the South’. He told his audience, including former, and future, US President Grover Cleveland, that southern blacks ‘were happy in their cabin homes, tilling their own land’. He rubbished the claims of northern commentators, such as O’Reilly, that blacks were marginalised or subject to regular violence. Black ‘agitators’, he declared, were responsible for spreading this falsehood among gullible or anti-southern journalists. Grady evidently told his audience what they wanted to hear and his speech was interrupted for applause at least twenty-nine times. Over the following days, newspapers in Boston and across the north extolled Grady’s speech and the promise it offered of a rapprochement between the north and the former confederacy. O’Reilly was one journalist who disputed this consensus. In The Pilot he chastised Grady and the attitude which the southerner represented, writing that: ‘Never did oratory cover up the weaker points of a repulsive cause so well…’ O’Reilly did more than editorialise and, in his paper, he printed a series of articles which disputed the claims advanced by Grady and which highlighted the realities of southern life. Throughout the 1880s black communities had to contend with increasing violence from white mobs. One particularly brutal occurrence was the massacre of eight black men by over one hundred whites in Barnwell County, South Carolina, during December 1889. O’Reilly responded to the event with one of his angriest editorials: The black race in the South must face the inevitable, soon or late, and the inevitable is - DEFEND YOURSELF. If they shrink from this, they will be trampled on with yearly increasing cruelty until they have sunk back from the great height of American freedom to which the war-wave carried them. And in the end, even submission will not save them. On this continent there is going to be no more slavery. That is settled forever. Not even voluntary slavery will be tolerated. Therefore, unless the Southern blacks learn to defend their homes, women, and lives, by law first and by manly force in extremity, they will be exterminated like the Tasmanian and Australian blacks. No other race has ever obtained fair play from the Anglo-Saxon without fighting for it, or being ready to fight. The Southern blacks should make no mistake about the issue of the struggle they are in. They are fighting for the existence of their race; and they cannot fight the Anglo-Saxon by lying down under his feet. This article brought O’Reilly much criticism across the United States, some of which he printed in The Pilot. In reply to a claim from the St. Louis newspaper Church Progress that: ‘It is neither Catholic nor American to rouse the negroes of the South to open and futile rebellion’ he wrote: ‘True, and the Pilot has not done so. We have appealed only to the great Catholic and American principle of resisting wrong and outrage, of protecting life and home and the honor of families by all lawful means, even the extremest, when nothing else remains to be tried.’ O’Reilly further defended his editorial by claiming that blacks in the south were ‘fighting for the existence of their race’ and that if they failed they would be ‘exterminated’. The reality of southern life was a topic that O'Reilly returned to on many occasions. 'All who teach are ours. The priests of all future dispensations shall be members of the press. Ours is the newest and greatest of the professions, involving wider work and heavier responsibilities than any other. For all time to come, the freedom and purity of the press are the test of national virtue and independence. No writer for the press, however humble, is free from the burden of keeping his purpose high and his integrity white. The dignity of communities is largely intrusted to our keeping; and while we sway in the struggle or relax in the rest-hour, we must let no buzzards roost on the public shield in our charge.' O’Reilly had a clear vision of how the press should function and from the beginning of his time with The Pilot in 1870 he used the newspaper to do battle on behalf of America’s underprivileged. In 1879 he gave a speech to the Boston Press Club in which he described this vision to his audience of fellow editors and reporters. In O’Reilly’s eyes, the journalist held an august and vital position in society. Journalism, he believed, should be something more than mere muck-raking and manufactured outrage. The press should seek to move beyond sensationalism and to explain the world to its readers in an honest and clear manner. By the 1880's O’Reilly had emerged as a consistent public adversary of racism and he was often asked by civil rights groups to speak or write on race-relations. He was, for example, an open opponent of anti-Semitism and, on one occasion, The American Hebrew magazine asked O’Reilly to provide his analysis of anti-Jewish sentiment in the United States. Yet, amid all O’Reilly’s writings and activity in support of minorities of one form or another, it was the issue of black civil rights to which he would most often return, although it had taken him a few years to clarify his thoughts on this subject. We will return to this issue in a later post.  Louise Imogen Guiney, circa 1893 (US Library of Congress). O'Reilly remained an opponent of women's suffrage throughout his life, although he argued for the protection of women's rights in the workplace. He hired women such as Guiney and Katherine Conway as journalists for The Pilot. Guiney dedicated her first book of poetry to O'Reilly. Louise Imogen Guiney, circa 1893 (US Library of Congress). O'Reilly remained an opponent of women's suffrage throughout his life, although he argued for the protection of women's rights in the workplace. He hired women such as Guiney and Katherine Conway as journalists for The Pilot. Guiney dedicated her first book of poetry to O'Reilly. Despite all O’Reilly’s writings in support of civil rights and in opposition to prejudice he would play a different role in the long-running campaign to obtain voting rights for women. Throughout his time with The Pilot O’Reilly was a consistent opponent of women’s suffrage. His attitudes to women's struggle to gain the vote are analysed in detail in my biography of O'Reilly. They were an amalgam of many influences, partly religious, and partly based on O'Reilly's view that society and civilisation was ultimately underpinned by violence. Society, he argued, was a fragile blend of competing interests, each of which were backed by men willing and able to fight for what they believed. It was those competing interests which were the driving force of history and if the disparate groups that formed the social order failed to compromise then violence was the inevitable result. According to O’Reilly, the delicate balance of society would be skewed by women’s suffrage. His reasoning was that women are physically the weaker sex so it was worse than futile to give women the vote. They would never be able to protect their interests through force and would be trampled upon by men. The ensuing disregard for law would set a brutal and dangerous precedent that would spread anarchy throughout the land. ‘A vote, like a law’, he once declared, ‘is no good unless there is an arm behind it; it cannot be enforced. This is a shameful truth, perhaps, but it is true.’ This belief caused O'Reilly to move away from principles that were otherwise central to his world view. Although he would not have seen it this way, O’Reilly was a man who toiled on behalf of so many of the disenfranchised groups of the United States but who was willing to deprive women of the chance to live a full life. In his defence of the Irish, blacks, Jews, and others O’Reilly was continually vigilant for those commentators and politicians who sought to limit the freedom of achievement of particular groups. This vigilance was absent when it came to suffrage for women and O’Reilly repeatedly resorted to listing virtues and characteristics that he believed were inherent to women and which made them perfectly suited to their historical mission as ‘queen of the household’. For O’Reilly they often seemed to be wholly defined by these supposed characteristics: "We want no contest with women; they are higher, truer, nobler, smaller, meaner, more faithful, more frail, gentler, more envious, less philosophic, more merciful - oh, far more merciful and kind and lovable and good than men are. Those of them that are Catholics, are better Catholics than their husbands and sons; those who are Protestants are better Christians than theirs. Women have all the necessary qualities to make good men; but they must give their time and attention to it while the men are boys." O’Reilly’s attitude would persist in the pages of The Pilot long into the future. James Jeffrey Roche, who joined the paper in 1883 and who later followed O’Reilly as editor of the paper, revered his friend and former boss. Roche followed his idol’s line on many issues, including that of women’s suffrage. The above passage from O’Reilly, he considered to be ‘one of the best ever’ responses to the supporters of women’s suffrage. O’Reilly, Roche, and others like them would remain unmoved by the arguments of women who sought to climb down from their pedestal and who refused to let such lists be the limits of their lives. If Cashman or any of them knows anything about Miss Woodman I wish they would write it or tell you what it is. Was the child born? That’s the principal thing I want to know.  There are no verified images of Jessie Woodman when she was a young woman. The above photo is of Catherine Pickersgill, Jessie's daughter. Catherine supposedly bore a striking resemblance to her mother (photo provided by Denise Moore, great-great grand daughter of Jessie Woodman). There are no verified images of Jessie Woodman when she was a young woman. The above photo is of Catherine Pickersgill, Jessie's daughter. Catherine supposedly bore a striking resemblance to her mother (photo provided by Denise Moore, great-great grand daughter of Jessie Woodman). During September 2015, a new exhibition opened in Millmount Museum, Drogheda. The exhibition titled 'Shall the punishment fall on the girl alone' was co-curated by Ian Kenneally and Sean Corcoran. It tells of a recently discovered letter, written by John Boyle O'Reilly, in which he reveals some extraordinary facts about his relationship with Jessie Woodman. This letter, entombed in a drawer for one-hundred and forty-five years, was recently rediscovered in San Francisco. John Boyle O’Reilly lived an epic life but in the exhibition we see him at his most vulnerable, amid a time of intense personal turmoil. The exhibition ran until November 2015. The fourteen months that O'Reilly spent in Western Australia have often dominated accounts of his life. Yet, that time, from January 1868 to March 1869, has always been a source of myths, misconceptions, and unanswered questions. During that time the twenty-four year old John fell in love with a woman named Jessie Woodman, the daughter of the head warden in O’Reilly’s convict camp. Rumours regarding this relationship were first made public by Michael Davitt during the 1890s in his book, Life and Progress in Australasia. Martin Carroll, an American historian, was the next person to examine this relationship in the early 1950s. Carroll interviewed descendants of Bunbury residents who knew O’Reilly in the 1860s and concluded that O'Reilly and Woodman did have an affair. The fact of a relationship was finally confirmed in 1989 by the Australian archivist Gillian O’Mara. During that year a slim notebook was given to the Battye Library in Perth which was signed ‘By John Boyle O’Reilly, 13 March sixty eight, in the bush near Bunbury’. O’Mara then deciphered the shorthand script through which O’Reilly had scrawled messages across the pages of the book. It was a log which O’Reilly kept from March onwards while in the convict depot. Unfortunately, it was not a diary and does not contain much personal information, being mostly poems that O’Reilly wrote while he was in Western Australia. Yet, it does establish that O’Reilly was involved with a local girl and contains the admissions that; ‘I am in love up to my ears’ and ‘It would take a saint to give her up’. That their relationship was physical was confirmed by his gripe that ‘I wish she was not so fond of kissing’. The newly discovered letter confirms the long-held suspicion that Jessie Woodman became pregnant during her relationship with O'Reilly. The exhibition details the contents of the letter and its ramifications for our understanding of O'Reilly. We know that John attempted suicide at the end of 1868 but the letter also hints that Jessie made an attempt on her life, perhaps as part of a pact. Jessie has remained a somewhat shadowy figure, her part in the story obscured by the fame which later enveloped O'Reilly. This exhibition provides a wealth of new information on Jessie and traces what happened to her in later years and what happened to her baby. Being an unmarried mother in nineteenth-century Australia would have marked Jessie as, to use the language of the time, ‘unfit’, ‘dissolute’, and of ‘dangerous character’. Not only could her pregnancy have resulted in social disgrace and marginalisation but there was also the possibility that the child could have been removed from her care. In March 1869, Jessie married a local man named George Pickersgill, a figure with whom she does not seem to have had a prior relationship. As O'Reilly suggests in the letter, this was done to save her name and that of her family. The discovery of this letter has become part of the John Boyle O’Reilly story. It provides us with a glimpse into a relationship which has remained veiled for over a century. More than that, the letter provides us with a starting point from which we can look at O’Reilly’s life and work in the context of this new knowledge. Perhaps Jessie Woodman haunted his thoughts for the rest of his days. How did Jessie Woodman deal with what happened? We may never know but there are indications, although no more than hints, that her marriage to Pickersgill was unhappy. Was she burdened with a life and a marriage she never desired? We can never know what scars were left upon O’Reilly’s psyche by his imprisonment and his enforced exile from Ireland. Through his own hand he almost lost his life in Western Australia. But he had escaped and grasped freedom to start his life again. Did that confrontation with his own mortality drive him onwards to achieve all that he achieved? Questions remain but the answers are worth pursuing since such research helps us to better understand our past and our present. As the exhibition shows, this remarkable letter answers many questions about O’Reilly but it also raises many more, adding new depths to a complex man and an incredible life-story.  The Gazelle, the ship that rescued O'Reilly from Western Australia (Roche, James Jeffrey, John Boyle O'Reilly - His Life, Poems, and Speeches, 1891). The Gazelle, the ship that rescued O'Reilly from Western Australia (Roche, James Jeffrey, John Boyle O'Reilly - His Life, Poems, and Speeches, 1891). As John Boyle O'Reilly stood on the deck of the Gazelle that first day of his voyage in early March 1869 he was probably unaware that he had joined an American industry which, according to the historian Margaret S. Creighton, ‘represented seafaring at its extreme’. Voyages routinely lasted for up to four years and whaling ships spent much of their time sailing through the most dangerous seas in the world. The heart of this global industry lay in the American port of New Bedford, Massachusetts and, each year, hundreds of whaling ships sailed from the so-called ‘Whaling City’. In August 1866 the Gazelle had been one of these ships and had been over two years at sea by the time it picked up O’Reilly. Throughout the nineteenth century these American ships mostly hunted four types of whale; the sperm whale, often referred to as a cachalot, was hunted mostly in the warm tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans; the right whale, hunted in the more temperate regions of the world’s oceans; the bowhead whale, also called the Arctic whale, which was hunted in the cold waters of the Arctic circle; and the humpback whale which was hunted all over the world but most heavily in the Atlantic Ocean. The bodies of the whales caught and slain by the whaling ships provided a range of important products. From the sperm whale came sperm oil. That oil was traditionally burned in lamps, especially street lamps, and had been used to illuminate cities across Europe and the United States for much of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century street-lamps were more often fired by gas but sperm oil remained in demand as a lighting fuel. Sperm oil was also used as machine lubricant. Other types of whale likewise furnished whale oil but these were heavier and of poorer quality than sperm oil and their oils were used more often as a lubricant rather than for illumination. The vagaries of fashion provided another ready market for whale products. A commercially important substance provided by Sperm whales was called spermaceti and was extracted from the animal’s head. The hunters would cut a large hole in a captured whale’s skull. One of the sailors would then crawl through this hole and manually remove the fluid. The spermaceti was placed in barrels for the rest of the voyage. This substance was used in the manufacture of candles and soaps. Sperm whales were also harvested for ambergris, an ash-coloured secretion found in the creature’s intestines. It was used as a fixative in perfumes. Other types of whales were killed for their baleen; a comb-like structure in the animal’s mouth which served to filter seawater for food. Baleen, also commonly known as whalebone, was light, strong, flexible and perfectly adapted to the manufacture of corsets, dress hoops, umbrellas, and other similar items. The most heavily hunted families of whales suffered grievous population losses from the eighteenth century onwards but they were to receive some respite in the second half of the nineteenth Century with the rise of kerosene as a competitor to whale oil. By 1858 the North American continent’s first oil well had been drilled at Oil Springs in Canada. During the following year the US petroleum industry began with the drilling of an oil well in 1859 at Oil Creek in Pennsylvania. The petroleum industry had a ready made market and over the following decades, as its production methods improved, the industry was able to massively increase the volume of petroleum produced. A further advantage for the petroleum industry was the fact that it could produce oil in the US whereas whaling firms had to purchase and equip ships which were then sent on hazardous multi-year voyages. As such, the owners of the oil wells were able to supply lighting oil at a far cheaper price than the whaling industry. Whalebone remained a commercially desirable product but it was whale oil that had been the mainstay of the industry. As the demand for whale oil steadily decreased, its price per barrel followed the same trajectory. Following these developments the whaling industry entered a precipitous decline during the 1860s and by 1869 only around 280 American whalers still plied their trade. These ships were crewed by approximately 8,000 men of whom O’Reilly was now one. On board the Gazelle were 31 crew; fourteen Americans, fourteen Portuguese, two Dutch and one Brazilian. Added to this mix was O'Reilly and the next few months were to prove to be a dangerous and transformative time for the young Irishman. 'O' Reilly was in the stable tightening his saddle girths and getting ready to mount and start off to the vice-regal lodge with a dispatch for the lord lieutenant from Sir Hugh Rose, the commander of the forces in Ireland. Byrne had just time to introduce us, and O'Reilly and I to make an appointment for the next evening, when he brought out his horse, sprang into the saddle, and was off. O' Reilly was then a handsome, lithely built young fellow…with the down of a future black moustache on his lip. He had pair of beautiful dark eyes, that changed in expression with his varying emotions. He wore the full-dress dark blue hussar uniform, with its mass of braiding across the breast, and the busby with its tossing plume, was set jauntily on the head and held by a linked brass strap, catching under the lower lip.'  John Devoy, seen here in later life (US Library of Congress). In 1865, Devoy recruited John Boyle O'Reilly in to the Irish Republican Brotherhood while the latter was still a serving member of the British army. John Devoy, seen here in later life (US Library of Congress). In 1865, Devoy recruited John Boyle O'Reilly in to the Irish Republican Brotherhood while the latter was still a serving member of the British army. John Devoy and O'Reilly first met in October 1865 while the latter was stationed in Dublin. Devoy, who had experience with the French Foreign Legion, was then engaged as a recruiter for the Irish Republican Brotherhood. At that time the IRB was working to enlist the many Irish soldiers in the British army into the Brotherhood. By autumn 1865, most of these IRB recruiters had been arrested and John Devoy was promoted to the role of chief recruiter. In his later memoir Devoy explained this new role: ‘I had some acquaintance with the army, through living near the Curragh camp, and, when all the ‘organizers’ for the army had been arrested or forced to remain ‘on their keeping,’ James Stephens, the chief executive of the Irish republic that was to be, appointed me ‘chief organizer’ for the British army.’ Through an acquaintance Devoy met O'Reilly at the Royal Barracks, later Collins Barracks, and informed him of the IRB's plans for revolution. The next day, O'Reilly took the IRB oath and joined Devoy in recruiting soldiers into the Brotherhood. It was a task in which O'Reilly was remarkably successful, convincing some eighty soldiers in the Tenth Hussars to take the Brotherhood's oath. The meeting with Devoy had a profound effect on O’Reilly’s life, sending the young soldier on a dangerous new path, a path that would lead to imprisonment, hard labour, and transportation to Australia. That was all in the future. O'Reilly survived his many ordeals and would meet Devoy again in the United States. By that stage O'Reilly had left the IRB but he would assist Devoy in the planning of the Catalpa rescue. That story will be the focus of another blog post. The poem was first published in 1886 as part of O'Reilly's final collection of poetry, In Bohemia. O’Reilly’s determination to address social problems in his poetry is the key theme of In Bohemia. In that sense it is similar to his earlier works. Yet, as a whole, the collection is of a more personal nature than his previous volume, The Statues in the Block. In poems such as ‘The Cry of the Dreamer’ and ‘In Bohemia’ O’Reilly is not looking down on events, as in poems such as ‘From the Earth, a Cry’, but is ensconced in the midst of the society which he is criticising. The poet is on the street and amongst the crowds and he does not like what he sees. An analysis of o'Reilly's work can be found in my biography of O'Reilly.

I'd rather live in Bohemia than in any other land; For only there are the values true, And the laurels gathered in all men's view. The prizes of traffic and state are won By shrewdness or force or by deeds undone; But fame is sweeter without the feud, And the wise of Bohemia are never shrewd. Here, pilgrims stream with a faith sublime From every class and clime and time, Aspiring only to be enroiled With the names that are writ in the book of gold; And each one bears in mind or hand A palm of the dear Bohemian land. The scholar first, with his book--a youth Aflame with the glory of harvested truth; A girl with a picture, a man with a play, A boy with a wolf he has modeled in clay; A smith with a marvelous hilt and sword, A player, a king, a ploughman, a lord-- And the player is king when the door is past. The ploughman is crowned, and the lord is last! I'd rather fail in Bohemia than win in another land; There are no titles inherited there, No hoard or hope for the brainless heir; No gilded dullard native born To stare at his fellow with leaden scorn: Bohemia has none but adopted sons; Its limits, where Fancy's bright stream runs; Its honors, not garnered for thrift or trade, But for beauty and truth men's souls have made. To the empty heart in a jeweled breast There is value, maybe, in a purchased crest; But the thirsty of soul soon learn to know The moistureless froth of the social show; The vulgar sham of the pompous feast Where the heaviest purse is the highest priest; The organized charity, scrimped and iced, In the name of a cautious, statistical Christ; The smile restrained, the respectable cant, When a friend in need is a friend in want; Where the only aim is to keep afloat, And a brother may drown with a cry in his throat. Oh, I long for the glow of a kindly heart and the grasp of a friendly hand, And I'd rather live in Bohemia than in any other land. In January 1868, John Boyle O'Reilly arrived in what was then the Penal Colony of Western Australia. He would spend a little over a year as a convict in the colony before he escaped to freedom aboard an American whaling ship. Australia, and convict life, were subjects that O'Reilly returned to many times in his writing and, today, he is regarded as an important author from that formative period in modern Western Australian history. His first volume of poetry, Songs from the Southern Seas, and Other Poems, was published in 1873 and contains the poem 'Western Australia'.

O BEAUTEOUS Southland! land of yellow air, That hangeth o'er thee slumbering, and doth hold The moveless foliage of thy valleys fair And wooded hills, like aureole of gold. O thou, discovered ere the fitting time. Ere Nature in completion turned thee forth I Ere aught was finished but thy peerless clime, Thy virgin breath allured the amorous North. O land, God made thee wondrous to the eye! But His sweet singers thou hast never heard; He left thee, meaning to come by-and-by. And give rich voice to every bright-winged bird. He painted with fresh hues thy myriad flowers, But left them scentless: ah! their woeful dole, Like sad reproach of their Creator's powers,-- To make so sweet fair bodies, void of soul. He gave thee trees of odorous precious wood; But, 'midst them all, bloomed not one tree of fruit. He looked, but said not that His work was good, When leaving thee all perfumeless and mute. He blessed thy flowers with honey: every bell Looks earthward, sunward, with a yearning wist; But no bee-lover ever notes the swell Of hearts, like lips, a-hungering to be kist. O strange land, thou art virgin! thou art more Than fig-tree barren! Would that I could paint For others' eyes the glory of the shore Where last I saw thee; but the senses faint In soft delicious dreaming when they drain Thy wine of color. Virgin fair thou art, All sweetly fruitful, waiting with soft pain The spouse who comes to wake thy sleeping heart. 'The City Streets' was published in 1886 as part of O'Reilly's final collection, In Bohemia. The poet journeys through a city and contrasts the lives of the rich and poor. Geographically, the two groups are only metres apart but socially they inhabit parallel universes. O’Reilly deplores the tendency of the powerful to claim that all crime results from the supposed ‘criminal taint’ of the poor and thus ignore the fact that theft and other offences are often a result of desperation and necessity: in the game of life 'the poor man’s son carries double weight'. This theme was threaded through his poetry, fiction and newspaper editorials: those on the bottom rungs of society were being punished not because of any inherent flaws in their character but through the bad luck of being born into poverty or into a country that had been colonised.

A CITY of Palaces! Yes, that's true: a city of palaces built for trade; Look down this street—what a splendid view of the temples where fabulous gains are made. Just glance at the wealth of a single pile, the marble pillars, the miles of glass, The carving and cornice in gaudy style, the massive show of the polished brass; And think of the acres of inner floors, where the wealth of the world is spread for sale; Why, the treasures inclosed by those ponderous doors are richer than ever a fairy tale. Pass on the next, it is still the same, another Aladdin the scene repeats; The silks are unrolled and the jewels flame for leagues and leagues of the city streets! Now turn away from the teeming town, and pass to the homes of the merchant kings, Wide squares where the stately porches frown, where the flowers are bright and the fountain sings; Look up at the lights in that brilliant room, with its chandelier of a hundred flames! See the carpeted street where the ladies come whose husbands have millions or famous names; For whom are the jewels and silks, behold: on those exquisite bosoms and throats they burn; Art challenges Nature in color and gold and the gracious presence of every turn. So the winters fly past in a joyous rout, and the summers bring marvelous cool retreats; These are civilized wonders we're finding out as we walk through the beautiful city streets. A City of Palaces!—Hush! not quite: a, city where palaces are, is best; No need to speak of what's out of sight: let us take what is pleasant, and leave the rest: The men of the city who travel and write, whose fame and credit are known abroad, The people who, move in the ranks polite, the cultured women whom all applaud. It is true, there are only ten thousand here, but the other half million are vulgar clod; And a soul well-bred is eternally dear—it counts so much more on the books of God. The others have use in their place, no doubt; but why speak of a class one never meets? They are gloomy things to be talked about, those common lives of the city streets. Well, then, if you will, let us look at both: let us weigh the pleasure against the pain, The gentleman's smile with the bar-room oath, the luminous square with the tenement lane. Look round you now; 'tis another sphere, of thin-clad women and grimy men; There are over ten thousand huddled here, where a hundred would live of our upper ten. Take care of that child: here, look at her face, a baby who carries a baby brother; They are early helpers in this poor plane, and the infant must often nurse the mother. Come up those stairs where the little ones went: five flights they groped and climbed in the dark; There are dozens of homes on the steep ascent, and homes that are filled with children—hark! Did you hear that laugh, with its manly tones, and the joyous ring of the baby voice? 'Tis the father who gathers his little ones, the nurse and her brother, and all rejoice. Yes, human nature is much the same when you come to the heart and count its beats; The workman is proud of his home's dear name as the richest man on the city streets. God pity them all! God pity the worst! for the worst are reckless, and need it most: When we trace the causes why lives are curst with the criminal taint, let no man boast: The race is not run with an equal chance: the poor man's son carries double weight; Who have not, are tempted; inheritance is a blight or a blessing of man's estate. No matter that poor men sometimes sweep the prize from the sons of the millionaire: What is good to win must be good to keep, else the virtue dies on the topmost stair; When the winners can keep their golden prize, still darker the day of the laboring poor: The strong and the selfish are sure to rise, while the simple and generous die obscure. And these are the virtues and social gifts by which Progress and Property rank over Man! Look there, O woe! where a lost soul drifts on the stream where such virtues overran: Stand close—let her pass! from a tenement room and a reeking workshop graduate: If a man were to break the iron loom or the press she tended, he knows his fate; But her life may be broken, she stands alone, her poverty stings, and her guideless feet, Not long since kissed as a father's own, are dragged in the mire of the pitiless street. Come back to the light, for my brain goes wrong when I see the sorrows that can't be cured. If this is all righteous, then why prolong the pain for a thing that must be endured? We can never have palaces built without slaves, nor luxuries served without ill-paid toil; Society flourishes only on graves, the moral graves in the lowly soil. The earth was not made for its people: that cry has been hounded down as a social crime; The meaning of life is to barter and buy; and the strongest and shrewdest are masters of time. God made the million to serve the few, and their questions of right are vain conceits; To have one sweet home that is safe and true, ten garrets must reek in the darkened streets. 'Tis Civilization, so they say, and it cannot be changed for the weakness of men. Take care! take care! 'tis a desperate way to goad the wolf to the end of his den. Take heed of your Civilization, ye, on your pyramids built of quivering hearts; There are stages, like Paris in '93, where the commonest men play most terrible parts. Your statutes may crush but they cannot kill the patient sense of a natural right; It may slowly move, but the People's will, like the ocean o'er Holland, is always in sight. 'It is not our fault!' say the rich ones. No; 'tis the fault of a system old and strong; But men are the makers of systems: so, the cure will come if we own the wrong. It will come in peace if the man-right lead; it will sweep in storm if it be denied: The law to bring justice is always decreed; and on every hand are the warnings cried. Take heed of your Progress! Its feet have trod on the souls it slew with its own pollutions; Submission is good; but the order of God may flame the torch of the revolutions! Beware with your Classes! Men are men, and a cry in the night is a fearful teacher; When it reaches the hearts of the masses, then they need but a sword for a judge and preacher. Take heed, for your Juggernaut pushes hard: God holds the doom that its day completes; It will dawn like a fire when the track is barred by a barricade in the city streets.  A scene from the 'Battle of Ridgeway', 1866 (US Library of Congress) A scene from the 'Battle of Ridgeway', 1866 (US Library of Congress) A two-day conference, literary evening, and associated events will be held over June 2-3, 2016, in Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada. This Conference, the first on this topic in Canada, will present a complete overview of the political climate on the Canada/US border in the 1860's through keynote speeches, panel discussions, and specialist information sessions. The presentations will focus on the events leading up to, and culminating in, the Battle of Ridgeway/Fort Erie June 2, 1866. The international group of presenters will include published authors and historians with expertise in the political, military, and social aspects of Canadian, Irish, and US history during the 1860's. The conference is intended to be a multidisciplinary event. The addresses and lectures will be augmented with art, music, and literature of the period. For more information, and to book tickets, see the official website. An estimated 200,000 Irish-born soldiers fought in the American Civil War (180,000 with the Union and 20,000 with the Confederacy). At the war's end there were tens of thousands of battle-hardened Irish veterans, as well as many officers from both the Union and Confederate armies. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, popularly known as the Fenians, had long hoped to utilise these soldiers for an incursion into Canadian territory that would be timed to coincide with a revolution in Ireland. Thus the British Empire would be engaged in two widely separated theatres of war. When it became apparent that the hoped-for rising in Ireland was not to happen during 1866 (a small-scale Irish rising would take place in 1867 but was defeated) the goal of the invasion was changed. The Fenians now hoped that they could engineer a border incident that would entangle British forces in a war with the United States. Consequently, the years 1866, 1870, and 1871, witnessed the various 'Fenian Raids' on Canada and we will discuss these events in a later post. John Boyle O'Reilly was a prisoner in Ireland during the 1866 raids, having been arrested in February of that year. O'Reilly, a soldier in the British army's 10th Hussars, had been secretly recruiting soldiers into the Irish Republican Brotherhood in advance of the planned Irish rising. When O'Reilly arrived in the USA in 1869, following his escape from an Australian penal colony, he would come to know many of the leaders and individuals who were active in 1866 and he would play an important role in the subsequent Fenian raid in 1870. His life-story, spanning both sides of the Atlantic, provides a means through which to untangle and better understand a period when Irish nationalists would seek to defeat the British Empire, not only in Ireland but also in what was to become modern Canada. Through studying O'Reilly and others, we can see how the histories of Ireland, Canada, the British Empire, and the United States overlapped and resulted in the extraordinary events that were the 'Fenian raids'. |

Ian Kenneally

Short articles about the life and times of John Boyle O'Reilly. Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|