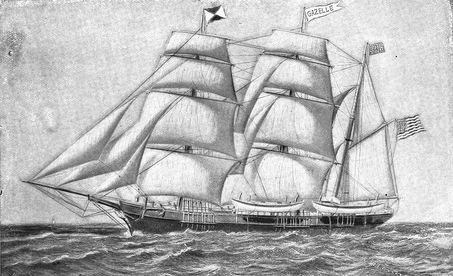

If Cashman or any of them knows anything about Miss Woodman I wish they would write it or tell you what it is. Was the child born? That’s the principal thing I want to know.  There are no verified images of Jessie Woodman when she was a young woman. The above photo is of Catherine Pickersgill, Jessie's daughter. Catherine supposedly bore a striking resemblance to her mother (photo provided by Denise Moore, great-great grand daughter of Jessie Woodman). There are no verified images of Jessie Woodman when she was a young woman. The above photo is of Catherine Pickersgill, Jessie's daughter. Catherine supposedly bore a striking resemblance to her mother (photo provided by Denise Moore, great-great grand daughter of Jessie Woodman). During September 2015, a new exhibition opened in Millmount Museum, Drogheda. The exhibition titled 'Shall the punishment fall on the girl alone' was co-curated by Ian Kenneally and Sean Corcoran. It tells of a recently discovered letter, written by John Boyle O'Reilly, in which he reveals some extraordinary facts about his relationship with Jessie Woodman. This letter, entombed in a drawer for one-hundred and forty-five years, was recently rediscovered in San Francisco. John Boyle O’Reilly lived an epic life but in the exhibition we see him at his most vulnerable, amid a time of intense personal turmoil. The exhibition ran until November 2015. The fourteen months that O'Reilly spent in Western Australia have often dominated accounts of his life. Yet, that time, from January 1868 to March 1869, has always been a source of myths, misconceptions, and unanswered questions. During that time the twenty-four year old John fell in love with a woman named Jessie Woodman, the daughter of the head warden in O’Reilly’s convict camp. Rumours regarding this relationship were first made public by Michael Davitt during the 1890s in his book, Life and Progress in Australasia. Martin Carroll, an American historian, was the next person to examine this relationship in the early 1950s. Carroll interviewed descendants of Bunbury residents who knew O’Reilly in the 1860s and concluded that O'Reilly and Woodman did have an affair. The fact of a relationship was finally confirmed in 1989 by the Australian archivist Gillian O’Mara. During that year a slim notebook was given to the Battye Library in Perth which was signed ‘By John Boyle O’Reilly, 13 March sixty eight, in the bush near Bunbury’. O’Mara then deciphered the shorthand script through which O’Reilly had scrawled messages across the pages of the book. It was a log which O’Reilly kept from March onwards while in the convict depot. Unfortunately, it was not a diary and does not contain much personal information, being mostly poems that O’Reilly wrote while he was in Western Australia. Yet, it does establish that O’Reilly was involved with a local girl and contains the admissions that; ‘I am in love up to my ears’ and ‘It would take a saint to give her up’. That their relationship was physical was confirmed by his gripe that ‘I wish she was not so fond of kissing’. The newly discovered letter confirms the long-held suspicion that Jessie Woodman became pregnant during her relationship with O'Reilly. The exhibition details the contents of the letter and its ramifications for our understanding of O'Reilly. We know that John attempted suicide at the end of 1868 but the letter also hints that Jessie made an attempt on her life, perhaps as part of a pact. Jessie has remained a somewhat shadowy figure, her part in the story obscured by the fame which later enveloped O'Reilly. This exhibition provides a wealth of new information on Jessie and traces what happened to her in later years and what happened to her baby. Being an unmarried mother in nineteenth-century Australia would have marked Jessie as, to use the language of the time, ‘unfit’, ‘dissolute’, and of ‘dangerous character’. Not only could her pregnancy have resulted in social disgrace and marginalisation but there was also the possibility that the child could have been removed from her care. In March 1869, Jessie married a local man named George Pickersgill, a figure with whom she does not seem to have had a prior relationship. As O'Reilly suggests in the letter, this was done to save her name and that of her family. The discovery of this letter has become part of the John Boyle O’Reilly story. It provides us with a glimpse into a relationship which has remained veiled for over a century. More than that, the letter provides us with a starting point from which we can look at O’Reilly’s life and work in the context of this new knowledge. Perhaps Jessie Woodman haunted his thoughts for the rest of his days. How did Jessie Woodman deal with what happened? We may never know but there are indications, although no more than hints, that her marriage to Pickersgill was unhappy. Was she burdened with a life and a marriage she never desired? We can never know what scars were left upon O’Reilly’s psyche by his imprisonment and his enforced exile from Ireland. Through his own hand he almost lost his life in Western Australia. But he had escaped and grasped freedom to start his life again. Did that confrontation with his own mortality drive him onwards to achieve all that he achieved? Questions remain but the answers are worth pursuing since such research helps us to better understand our past and our present. As the exhibition shows, this remarkable letter answers many questions about O’Reilly but it also raises many more, adding new depths to a complex man and an incredible life-story.  The Gazelle, the ship that rescued O'Reilly from Western Australia (Roche, James Jeffrey, John Boyle O'Reilly - His Life, Poems, and Speeches, 1891). The Gazelle, the ship that rescued O'Reilly from Western Australia (Roche, James Jeffrey, John Boyle O'Reilly - His Life, Poems, and Speeches, 1891). As John Boyle O'Reilly stood on the deck of the Gazelle that first day of his voyage in early March 1869 he was probably unaware that he had joined an American industry which, according to the historian Margaret S. Creighton, ‘represented seafaring at its extreme’. Voyages routinely lasted for up to four years and whaling ships spent much of their time sailing through the most dangerous seas in the world. The heart of this global industry lay in the American port of New Bedford, Massachusetts and, each year, hundreds of whaling ships sailed from the so-called ‘Whaling City’. In August 1866 the Gazelle had been one of these ships and had been over two years at sea by the time it picked up O’Reilly. Throughout the nineteenth century these American ships mostly hunted four types of whale; the sperm whale, often referred to as a cachalot, was hunted mostly in the warm tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans; the right whale, hunted in the more temperate regions of the world’s oceans; the bowhead whale, also called the Arctic whale, which was hunted in the cold waters of the Arctic circle; and the humpback whale which was hunted all over the world but most heavily in the Atlantic Ocean. The bodies of the whales caught and slain by the whaling ships provided a range of important products. From the sperm whale came sperm oil. That oil was traditionally burned in lamps, especially street lamps, and had been used to illuminate cities across Europe and the United States for much of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century street-lamps were more often fired by gas but sperm oil remained in demand as a lighting fuel. Sperm oil was also used as machine lubricant. Other types of whale likewise furnished whale oil but these were heavier and of poorer quality than sperm oil and their oils were used more often as a lubricant rather than for illumination. The vagaries of fashion provided another ready market for whale products. A commercially important substance provided by Sperm whales was called spermaceti and was extracted from the animal’s head. The hunters would cut a large hole in a captured whale’s skull. One of the sailors would then crawl through this hole and manually remove the fluid. The spermaceti was placed in barrels for the rest of the voyage. This substance was used in the manufacture of candles and soaps. Sperm whales were also harvested for ambergris, an ash-coloured secretion found in the creature’s intestines. It was used as a fixative in perfumes. Other types of whales were killed for their baleen; a comb-like structure in the animal’s mouth which served to filter seawater for food. Baleen, also commonly known as whalebone, was light, strong, flexible and perfectly adapted to the manufacture of corsets, dress hoops, umbrellas, and other similar items. The most heavily hunted families of whales suffered grievous population losses from the eighteenth century onwards but they were to receive some respite in the second half of the nineteenth Century with the rise of kerosene as a competitor to whale oil. By 1858 the North American continent’s first oil well had been drilled at Oil Springs in Canada. During the following year the US petroleum industry began with the drilling of an oil well in 1859 at Oil Creek in Pennsylvania. The petroleum industry had a ready made market and over the following decades, as its production methods improved, the industry was able to massively increase the volume of petroleum produced. A further advantage for the petroleum industry was the fact that it could produce oil in the US whereas whaling firms had to purchase and equip ships which were then sent on hazardous multi-year voyages. As such, the owners of the oil wells were able to supply lighting oil at a far cheaper price than the whaling industry. Whalebone remained a commercially desirable product but it was whale oil that had been the mainstay of the industry. As the demand for whale oil steadily decreased, its price per barrel followed the same trajectory. Following these developments the whaling industry entered a precipitous decline during the 1860s and by 1869 only around 280 American whalers still plied their trade. These ships were crewed by approximately 8,000 men of whom O’Reilly was now one. On board the Gazelle were 31 crew; fourteen Americans, fourteen Portuguese, two Dutch and one Brazilian. Added to this mix was O'Reilly and the next few months were to prove to be a dangerous and transformative time for the young Irishman. |

Ian Kenneally

Short articles about the life and times of John Boyle O'Reilly. Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|